Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch is one of the most innovative and influential artists of Modernism. He experimented with new techniques, and he developed a psychologically charged and expressive style to transmit emotional sensation. He fought for what he believed in, even though he – at times – met massive critique.

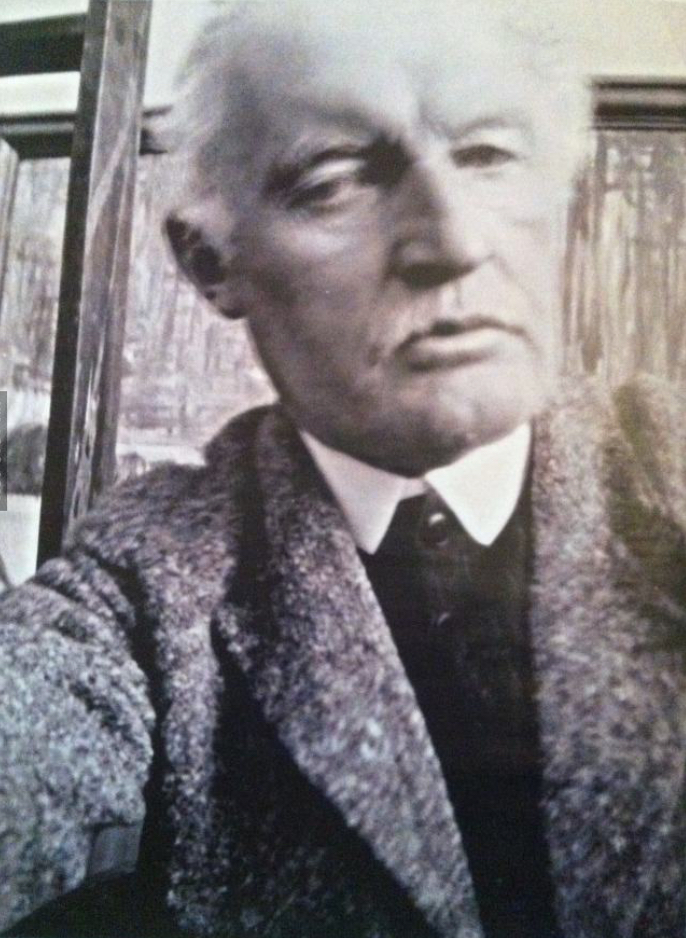

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait in Front of the House Wall, 1926 © Munch Museum/Munch-Ellingsen Group/BONO

For us today, it may be hard to understand that some people got really offended by his way of painting. People were not used to bold, vital brush strokes, dripping paint, scratching in the paint and canvas, and parts of the canvas hardly being painted at all – techniques that Munch used to express his true feelings. In some of the first exhibitions, people were litterally laughing of his paintings, and stong debates followed.

Part of the bohemian Kristiania, exhibition closed due to public reactions, a gunshot injury, strong feelings, strong meanings – and expressing them clearly… Read on to learn more about his life!

Born in Norway the 12th of December 1863, Edvard seemed so weak that he was baptised at home. Illness and death were strongly present in his life. When he was five, his mother died from tuberculosis. Later he lost his sister Sophie, and he himself suffered from chronic asthmatic bronchitis. In paintings such as The Dead Mother, Death in the Sickroom and The Sick Child, he expressed his feelings related to these experiences.

Edvard Munch, The Sick Child, 1907 © Munch Museum/Munch-Ellingsen Group

In 1880, after training as an engineer for one year, Munch decided that painting would be his life’s work, and he enrolled at the Royal School af Art and Design in the capital Kristiania (now Oslo). He rented a studio together with six colleagues. The young painters recieved instruction from the well-known and respected naturalist painter Christian Krohg. The form and subjects of Munch’s paintings from that time were clearly influenced by Krohg and by naturalism.

In the Autumn Exhibition in 1886, Munch exhibited one of his main works, the Sick Child. The sketch-like execution created great indignation. His rough technique was both criticized and laughed about. At a later Autumn Exhibition, Munch obviously found the whole show extremely booring, stating that

The Autumn Exhibition is more and more like a desert – a place where the audience has nothing to be angry about, but then again, nothing to be touched by

Edvard Munch

In 1889, Munch organized the first solo exhibiton ever held in Kristiania. In 1892, Munch was invited to exhibit in Berlin. His exhibition caused so many strong reactions that the exhibition closed after one week. Munch immediately sent the exhibit on to Düsseldorf and Cologne, and he also rented a space to show it again in Berlin.

Munch lived many years of his life abroad, amongst other in Berlin and Paris, where his circle consisted of painters, poets and composers. They were interested in the creative and destructive power of love, and in femininity and masculinity, as well as intellectuals such as Schopnhauer and Nietzsche. At the turn of the century, Munch gradually came to be a recognised and debated artist. The National Museum bought several of his works.

Interested as he was in new techniques, Munch bought his first camera in 1902. He was also very fascinated by the moving pictures.He often went to the cinema, and he bought his own film camera in 1927. He took still pictures of himself holding the camera with an outsteched arm – just like the selfies “everybody” is doing today.

The summer of 1902, Munch had a gunshot injury to his left hand in connection with his breakup with Tulla Larsen. He returned to this event repeatedly in subsequent years. Just at he returned to some other motives over and over again.

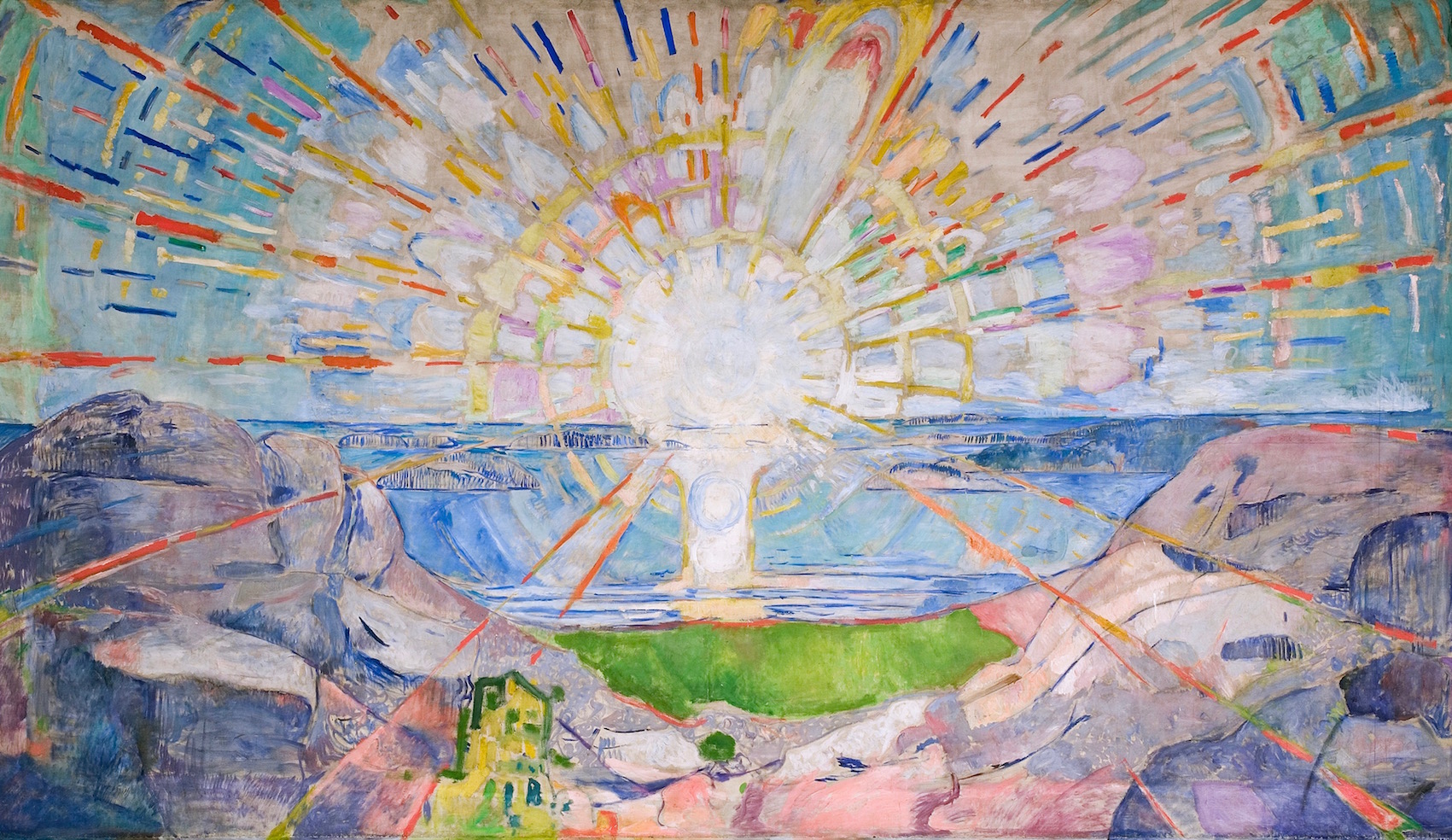

During the autumn of 1908, Munch had a breakdown and spent the following eight months in a clinic. After many years abroad, Munch then moved to Kragerø, at the sea side in the south of Norway. His reunion with Norwegian nature resulted in a new interest in harmony and classical composition. This manifested itself in a multitude of landscapes executed with vital brush strokes in a new, monumental style.

Munch fought for what he believed in. In 1909, Munch signed up for the competition for the decoration of the Univeristy Aula. To have enough space to produce the large decorations, he had to use untraditional methods, including building an outdoor studio. It was not until 1914, after many discussion and a lot of work, that the University accepted Munch’s drafts. The Aula decorations were completed in 1916, and include the monumental paintings History, The Sun and Alma Mater.

Edvard Munch: The Sun, 1911 © Munch m/Munch Museum/Munch-Ellingsen Gruppen

In 1912, Munch participated in an exhibition with van Gogh, Gauguin, Picasso and Cezanne, of which he wrote

All the wildest things that have been painted in Europe are collected here. I am practically a pale classicist

Edvard Munch

In 1916, Munch bought the property Ekely on the outskirts of Kristiania (now Oslo). He lived at Ekely for the rest of his life. He built several large outdoor studios on the property. Some of Munch’s paintings have been out in all kinds of weather.

Munch contracted an eye disease in 1930. By painting and drawing what he saw through the sick eye, he is revealing himself as a true modernist.

In 1937, 82 of Munch’s works were confiscated from German collections and labelled “degererate”. Many of Munch’s works were repatriated from Germany and auctioned off.

In his will, Munch left all his artwork that was in his own possession to Oslo municipality. During the last years of his life, Munch made several revealing self-portraits, showing an old man facing death. The 23rd of January 1944, Munch died quietly at Ekely. He left approximately 1.000 paintings, 15.400 prints, 4.500 watercolours, drawings and six sculptures, as well as writings and literary notes to the City of Oslo.